Transferring from the Miami Dade Honors College to Princeton University has been one of the best experiences of my life and attending Princeton has been a lifelong dream come true. However, at first, I didn’t know what to expect of Ivy League coursework. I questioned if my educational background as a community college student was enough to succeed at Princeton. As you prepare to make this transition, you might also have these concerns, but as a senior and after two years at Princeton, I can assure you that you are in great hands.

As part of Princeton’s second transfer cohort since the program’s relaunching in 2018, I’ve come to appreciate this University’s transfer program because it’s unlike any other in the country. With each cohort amounting to just a handful of students, we all receive personalized advising resources from the program’s director, Dr. Keith Shaw. By taking a transfer-based writing seminar course during our first semester with Dr. Shaw, the program offers opportunities to have regular check-ins with our adviser. Moreover, the program also integrates resources provided by the Scholars Institute Fellows Program (SIFP) , which assists first-generation and/or lower income students in their transition to Princeton. The transfer program also introduces students to the McGraw Center for Teaching and Learning and Writing Center, which offer tutoring and essay advising sessions.

Taking advantage of these resources has made the transition to a major four-year institution so much easier. Rather than being thrown into a large transfer cohort, we’re guided each and every step of the way as we take on challenging classes and begin to engage in unique extracurricular opportunities. In a way, the transition is almost seamless. The program equips you with the necessary resources to easily integrate into Princeton’s broader student body, while adapting to the academic rigor.

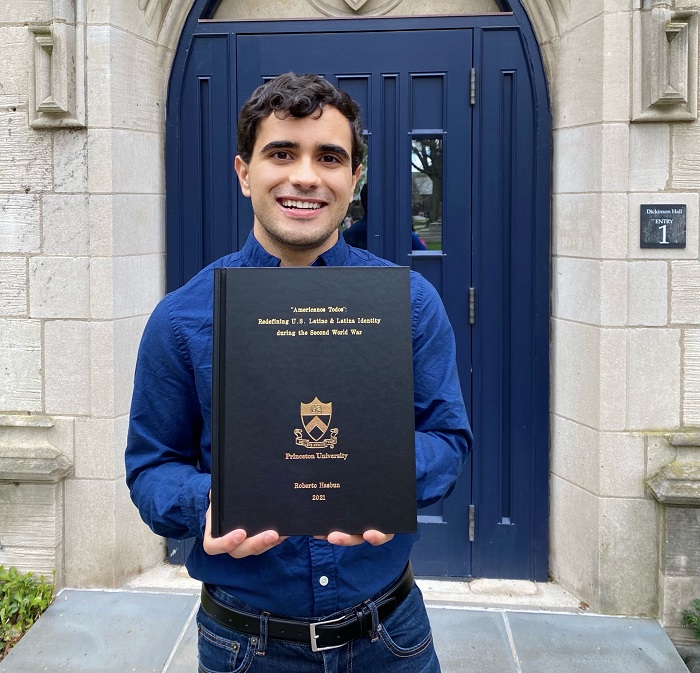

If it were not for the program’s one-on-one guidance and countless resources, I would not have been able to take advantage of Princeton’s many extracurricular opportunities. A week into my very first semester, I began volunteering for the PACE Center’s ESL El Centro program, in which I taught several weekly English classes to Spanish-speaking members of our community. I felt as though I was able to balance my extracurricular commitments with a challenging set of courses. However, a few weeks into my second semester, the COVID-19 pandemic upended my plans and routine, as it did for countless other people. I struggled to find worthwhile summer internships and fellowships after evacuating campus and self-isolating at home in Miami, Florida. Yet, after having engaged for at least a full semester’s worth of coursework and having built connections with several faculty members, I found myself working for two different professors as a research assistant. Throughout the summer, I helped curate research data and built several coding data frames.

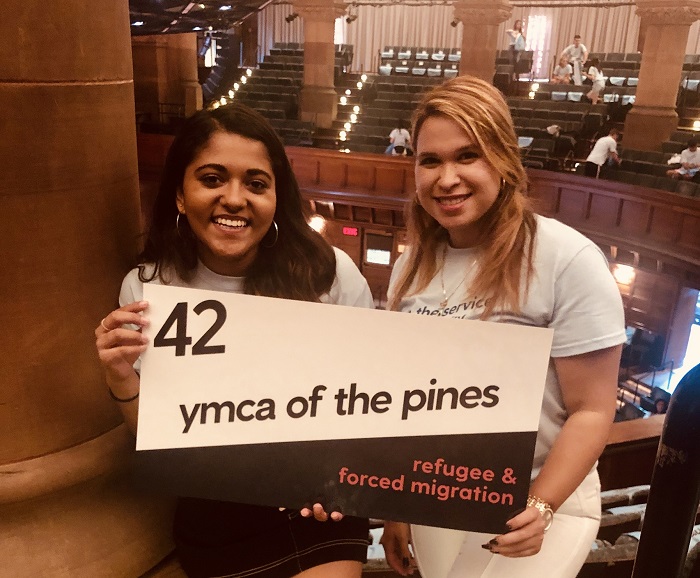

During that time, I also led the founding of the Princeton Transfer Association as the club’s president. Through the group, we have worked to further facilitate incoming transfer students’ transition by offering experienced transfer students’ insights during the orientation process and fostering a sense of community between each transfer cohort with community-building events. Additionally, Princeton's opportunities are available to all of its students, including transfers. At the start of my second year, I was also selected by one of Princeton’s most selective public policy fellowship programs, Scholars in the Nation’s Service Initiative (SINSI). The program offers about six students every year the opportunity to partake in an internship with a federal government agency. SINSI helps students interested in public service and policy find a way to begin engaging with the federal government.

Princeton’s transfer program offers a unique opportunity for students to not only make a transition from community college to a four-year university, but it also helps students thrive in the process. The transfer program has created an environment in which students from any academic discipline and background can expect to overcome the academic obstacles within the classrooms of a world-class institution, while also benefiting from unmatched professional development opportunities.