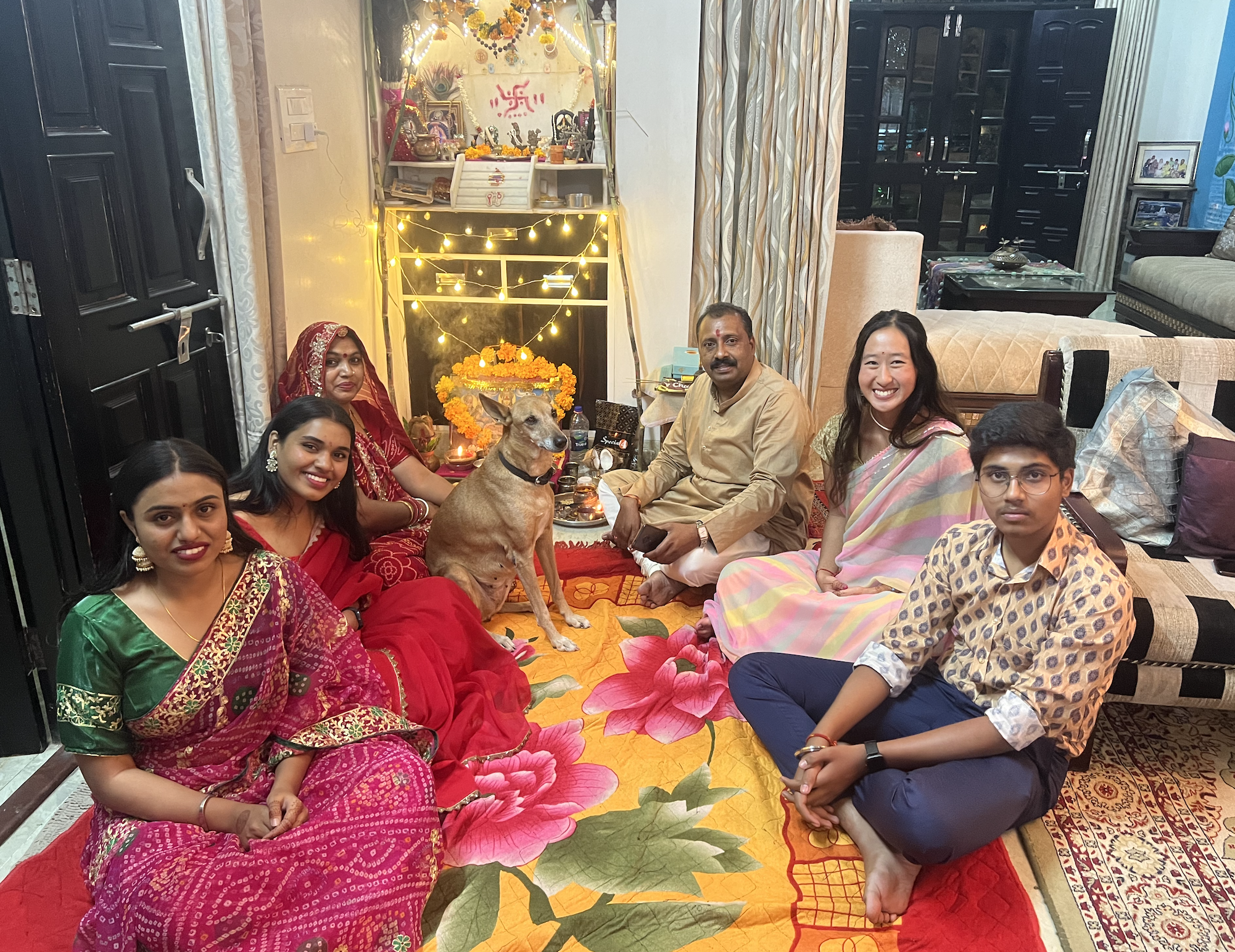

The summer after my high school graduation was a time marked by an incessant flow of questions, as everyone I knew sought to understand the reasons behind my decision to go on a gap year and live in India for 9 months. "Why go now?" "Aren't you concerned about missing out on college life?" "Do you think you'll be able to catch up on the academics and knowledge you might lose during your time away?"

And the truth is, answering these questions wasn’t easy. Deep down, I always knew that I wanted to take a gap year dedicated to travel and service, but I never really knew what that would entail. I was worried about what it would be like to spend so much time away from school, only to dive headfirst back into the whirlwind and fast-paced environment of Princeton.

But looking back, those questions should never have revolved around what I would potentially “lose” or need to “catch up on” during my year abroad. Instead, they should have focused on the self-discovery, cultural immersion, and personal growth that awaited me.

Bridge Year afforded me a unique opportunity to learn and embrace experiences that never would have been possible had I gone straight to college. Throughout the year, I encountered moments of joy, sadness, and adversity, but good or bad, each of these emerged as invaluable moments of learning. Instead of missing out on a year of school, I gained a series of lessons that could never have been taught to me in a classroom. These lessons, both positive and challenging, have shaped me in ways I couldn't have imagined, and I will carry them with me every day at Princeton and beyond.

Lesson #1: Kindness is a universal language

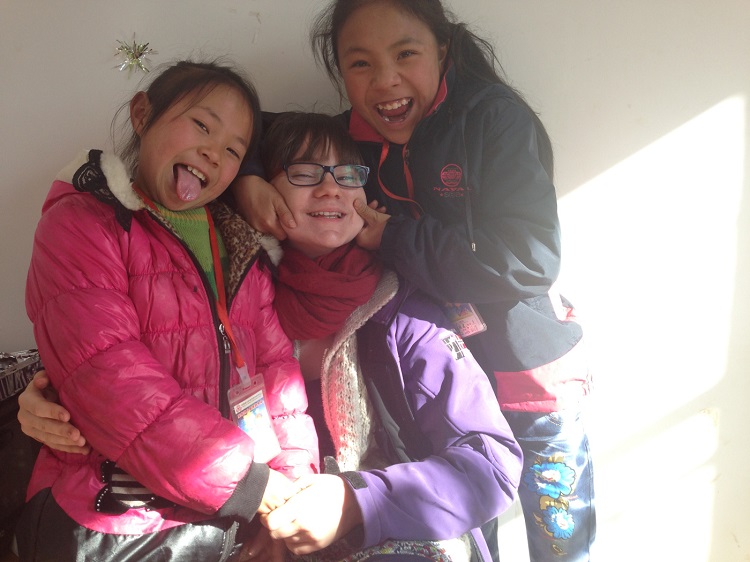

My first experience living in a homestay was nerve-wracking. It was only the third week in India, during our Fall Enrichment Program, when I found myself seated at a table in Sikkim with my Ama (homestay mom) and Isabella, my 6-year-old homestay sister. They only spoke Nepali, a language which I unfortunately knew none of at the time. I vividly remember the excruciatingly awkward nights spent trying to decipher each other’s words, often ending in confusion and uncomfortable silences. This kind-hearted family was gracious enough to invite me into their home and treat me like their own, and yet I couldn’t communicate with them, get to know them, or express my thanks. I yearned to find a way to tell them all the things I wanted to say. One day, when we were walking through the bustling market streets, Isabella extended her hand towards mine, and in an instant, I tightly embraced it. The trust that I felt from her in that moment filled my heart with joy. That evening, my Ama invited me into the kitchen when she was making dinner and guided me through the intricate process of rolling chapati dough. But my novice attempts resulted in amusingly misshapen creations that elicited a slew of laughter from the both of us. It was a shared experience filled with happiness and camaraderie, and I instantly felt closer to her. Throughout the rest of the year, every interaction I had living in a homestay showed me how actions alone could communicate what words never could. Whether it be a fresh cup of chai, a home-cooked meal, or a warm embrace, their actions spoke volumes. In those moments, I realised that true communication resides in the genuine acts of kindness, the shared experiences, and the unwavering support that we offered one another. Those actions formed an unspoken language, creating the connection that kept us close until now despite being so far apart.

Lesson #2: You are your own best company

Throughout the year, on most evenings, you would have found me in the corner of a garden filled with stone sculptures and willow trees, sitting with a lump of clay or a block of marble, trying to transform it into something new. For my Bridge Year Independent Enrichment Activity, I chose stone carving - a rich tradition that has shaped India’s architecture and artisanal work for centuries. When I arrived at this art studio along the lake, I immediately fell in love with the peace and tranquillity of the space. I spent 5-6 hours there every afternoon, getting completely lost in my work and my thoughts, slowly chipping away at the marble. I discovered a corner of the city that I could make my own, and in that process, I also discovered new parts of myself. I grew comfortable with my inner monologues, my irrational fears, and my incessant ramblings, and found refuge in this space I had created to just unapologetically embrace myself and find comfort in solitude. It is no secret that Princeton can sometimes be a lonely place, and so I reflect on my stone carving journey as a reminder to embrace the value of finding company with oneself and appreciate the beauty of solace and introspection—a realisation that has since become a lifeline for me, keeping me afloat in moments when I’m left on my own.

Lesson #3: How to be unconditionally compassionate

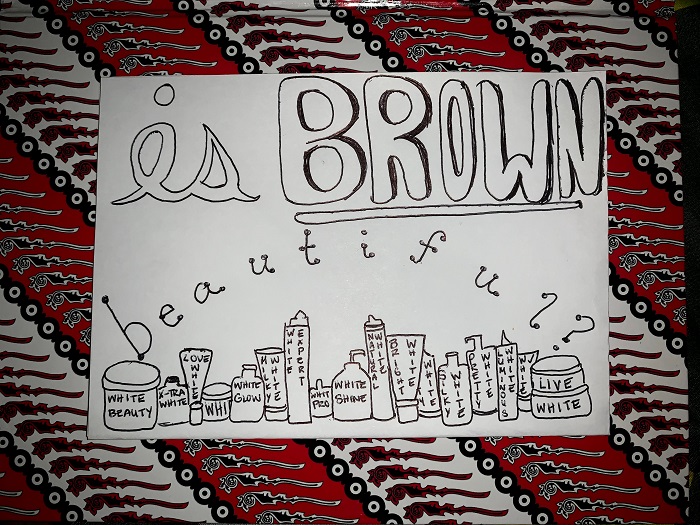

Living in India as someone born and raised in Hong Kong raised questions about my personal identity in the context of China-India relations and border tensions. Spending time out in public and teaching large classes of local students, I had to deal with misinformation-driven microaggressions and discrimination on a regular basis. Although this was difficult and upsetting, it also led me to realise how an increasingly polarised political landscape can foster echo chambers that enable one-sided thinking, manifesting into a form of ignorance that limits empathy and understanding. Acknowledging this, I chose to extend compassion and forgiveness towards those who held misconceptions about me. I practiced compassion by sharing my experiences and engaging in dialogue, aiming to bridge these misunderstandings and share my culture more honestly and authentically. Although this wasn’t easy, I felt comforted by the wise words of Bridge Year Program alumna Yun-Yun Li '17, who gave a speech at our send-off reception with advice that served as a consolatory guide throughout my time in India: “Learn to be able to hold two (or more) contradicting truths in your heart and mind at the same time, and still be able to move forward.” Even though it is true these interactions were challenging, hurtful, and wrong, it is also true that suffering becomes more approachable in a landscape of compassion. So, as I chose my battles and navigated the uncertainties of the year, I tried to remember to always give myself the grace and seek the acceptance and strength needed to continue moving forward—this valuable lesson remains a guiding principle to this day, empowering me to overcome obstacles and continue my journey, no matter what lies ahead.

At the end of the day, Bridge Year isn’t for everyone, but if you choose to embark on this journey, I can promise you that it will offer you lessons and discoveries that no other course at Princeton will. Bridge Year is a unique opportunity to immerse yourself in a new culture, confront challenges head-on, and expand your horizons in ways that traditional academic pursuits cannot replicate. Embracing the Bridge Year experience will not only shape your time at Princeton but also transform your perspective, inspiring a lifelong commitment to global engagement, personal growth, empathy, and a hope for learning more about yourself, others, and the world we live in.