The bright hours of a given day is the time when fears are abated, work is done and things illuminated. Light is the metaphor for intelligibility, knowing and comprehension, though too much leads to disenchantment, a tyranny of rationalism. Fortunately each day’s hours of light gives way to hours of darkness. The opaque shroud of the night is when myth returns, magic disturbs reason and the all-seeing gaze of the day hesitates in the face of ambiguous shadows (are they friends or foe?).

While it may seem obvious, the difference between day and night is luminance—the amount of light filling a certain area. So if you want to suggest day makes an area light then night makes it dark. An obvious point, but to make it so has not always been as easy as using a camera, whose basic “materials” are light and shadow.

Currently on view in the Princeton University Art Museum are representations of the night by artists from the 15th to 18th century, Durer to Goya, in etching and engravings. The mystery, drama and wonder occurring in these nights are in part conveyed by the limitations and possibilities of these mediums as the artist tries to show something of what happens under the moon and stars.

Etchings and engraving are both intaglio-printing processes. Instead of relief printing like woodcuts, in which an image is carved into the wood, inked, then stamped onto paper, in intaglio processes the paper is pressed into hollowed out drawings on metal (usually copper) plates. An engraver carves directly into the metal plate with various tools, then fills the carved lines with ink. An etcher covers his plate in wax, then draws his image upon the wax consequently removing the wax he draws on. The plate is then dipped in acid and the acid hollows out the area where the wax was removed to make the drawing. One important difference in these processes is that the engraver has straighter cleaner lines where the etcher has a freedom akin to pencil on paper.

One of the most intricate engravings on view, and perhaps the most fantastical of nights is Giorgio Ghisi’s "Allegory of Life" (1561). In it a man is huddled by a tree under dark skies and a crescent moon. The sharp lines possible with engravings make up a particularly jagged and barren landscape. He reaches desperately toward a goddess, who stands far away from him under light and surrounded by a robust forest. His chances of rescue appear slim, for he is surrounded by strange and hostile creatures—large carnivores fish, serpentine men and reptilian birds are only a few of threats closing in on him.

Though far less mythical, Jan van de Velde still conveys something of wonder in his early-17th century engraving "Shrove Tuesday." Here a more congenial darkness has descended on and around a Dutch town. It is the night of celebration before many nights of restraint during Lent. A crowd has gathered around a woman beating a drum. Men and women hold a reserved joy to her tune, while small children dance eagerly to the sound. All this is made visible by the small glow of a candle lantern, bright in the center and casting a fleeting light on the periphery members of the crowd.

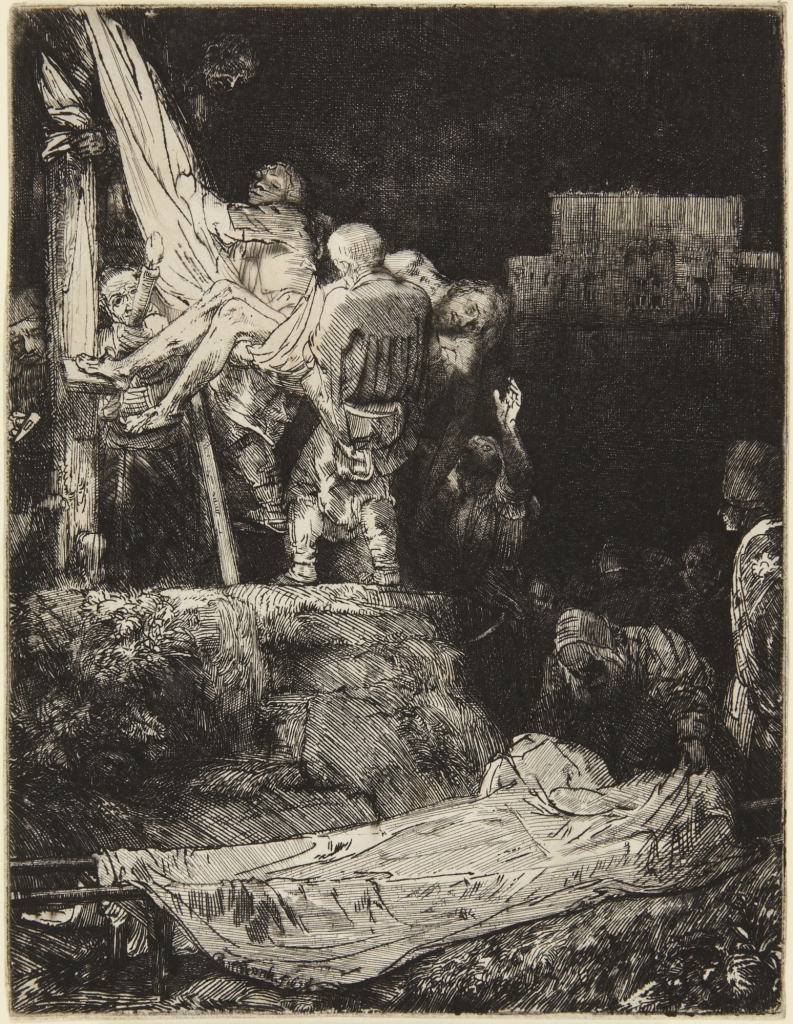

Rembrandt’s "Descent from the Cross by Torchlight" (1652) is also illuminated by a single light, though here the variability in line shape, depth and lucidity inherent in etching is used to make shadows and light that are much more furtive and tense than in van de Velde’s quaint genre scene. Several men bring Jesus’s lifeless body off the crucifix where he died during the day. There is an urgency and haste to their work as they rush to be gone before daybreak. At the composition’s bottom an elderly man sets the white sheets of the litter so that the body can be transported to a tomb where he of course will rise again.

However, at least in developments of etchings and engraving presented in the exhibit, Jesus is not resurrected. Two of the last four nights take us to the frolics of two men in a Dutch interior and then to the captivating experiments of a scientist who will show his audience the consequence of low air pressure upon a bird captured in his pneumatic glass invention. Something strange persists even in these secular scenes suggesting the continued belief and feeling in a seemly magical captivation and enchanted imagining.

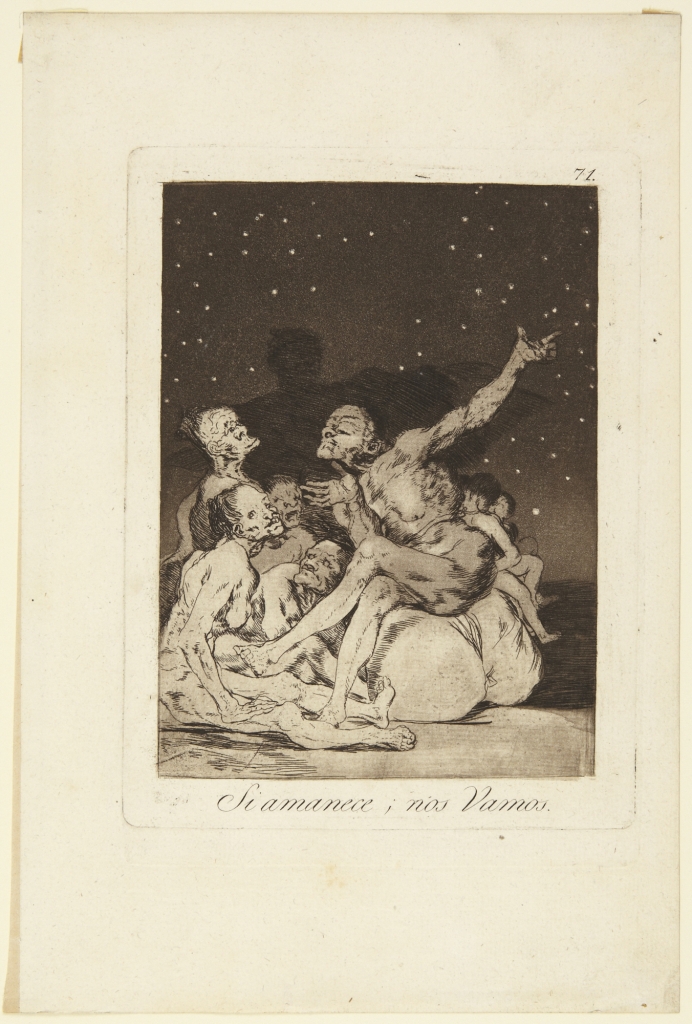

That legendary creatures still roam the nights of modernity is the final message of the exhibit that ends with an etching from Goya’s series of etchings called "Los Caprichos." Several grotesque figures sit under a starry sky below the visage of an ominous spectral being. One of the figures raises her hand, snapping to indicate something. She says the title of the work, “Si amanece, nos vamos” – “When day breaks we will be off.” But just wait until that day is over and again we can begin to find out what happens in the night.