Bridge Year is often seen as a magical experience where students are able to take a year off to travel the world on Princeton’s dime. That’s how I saw it. I was convinced about the opportunity to learn and grow by being immersed in the culture. Plus, I wanted to take advantage of a free travel opportunity and get out of the confines of New Jersey, especially after feeling senior year burnout. And part of me desperately needed time to figure out more about who I was– Princeton was offering that opportunity.

For some students, Bridge Year is the ultimate highlight of their Princeton experience. For others, not so much. Despite its glowing reviews, Bridge Year isn’t always sunshine and happy memories, yet those are the memories often communicated. The expansive and fast-paced nature of the program allows students to focus on the highlights. The program is broken into short-term travel (at the beginning, over Winter break, and the final month) which allows you to rapidly immerse yourself in different cultures and learn more about the history of the place you are in. Our group traveled to Indonesia on the shores of Banyuwangi, through the farms of Flores, up to the peak of Dieng, to the waterfalls of Sumba and more. Then for the majority of the program, my group and I lived in Jogja with our own individual homestay families, interned at an NGO, took language classes, attended speaker events or activities put on by the staff members, and took an extracurricular class that was rooted in some aspect of Indonesian culture (mine was silversmithing). At my NGO, I attended different events surrounding children's rights and assisted with research surrounding sex trafficking— a heavy yet important experience. Beyond all of those activities, I was free to explore the city and myself.

Because of the freedom to explore, many students on the trip face identity conflicts. In all fairness, identity conflict is a part of life. Bridge Year’s program design allows students to have time to reflect deeply on themselves, accelerating identity conflict and growth. Without academic rigor and structure, our brains can run free to think critically and deeply about ourselves. With the right support, this can be healthy.

For me, I struggled with being visibly brown: I am a first-generation Bangladeshi-American and a Muslim. Growing up, my hometown is known to be “accepting, diverse, and liberal,” but lacked a significant South Asian or Muslim population. As one of the few, I learned to compartmentalize the subtle racism and Islamophobia I faced to keep moving forward.

Bridge Year forced me to unpack all of it. Every day, I was forced to confront my identity because of other people. Instead of compartmentalizing, I had time to think about it.

At the start of the trip, whenever someone mentioned Islam, my group turned to me. At first, I was happy to fill in the gaps in their knowledge, but it soon hurt to hear their misconceptions about our traditions and beliefs.

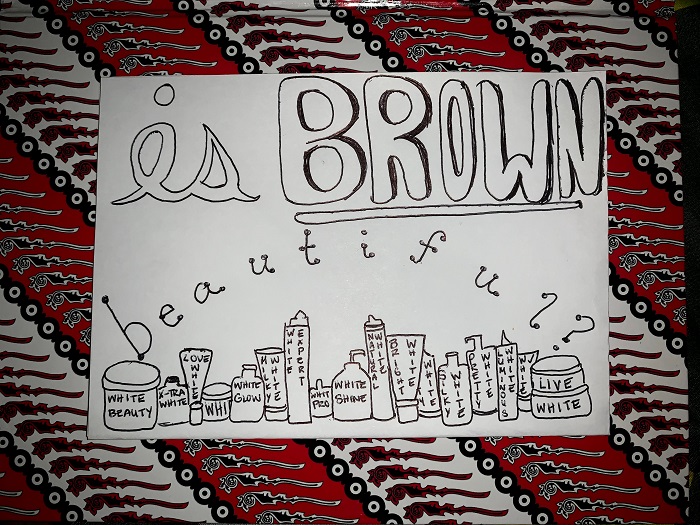

As we settled into our long-term homestays, I felt pressure from the rest of the community. Taxi drivers would always question where I came from, to the point where my group and I had a running joke: to answer with random places around the world. At events, locals would often question my identity– “Is she really American?” and only dropped the subject when my white peers spoke up for me. Sometimes, local Indonesians didn’t bother to include me among my peers. I learned to stand in the middle of the group to avoid being cut off at doors and in lines. Other times, people asked if I was the instructor’s daughter, despite us bearing no resemblance besides our skin tone. Further, I was constantly offered whitening soaps and products. Everyone I interacted with had some opinion on my skin, which took away from my agency in how I viewed my heritage and identity.

Yet these reactions came with perks. I could blend in more easily than my peers, avoiding scams and harassment– as long as I kept my mouth shut. As a Muslim, I felt another degree of connection to homestay families whenever they had a communal prayer. Despite these benefits, I fixated on the negative experiences, as is natural. Eventually, I grew to hate being brown.

Seeking help never felt obvious. The advising resources provided by Princeton were in a completely different time zone and I didn’t feel like a real Princeton student or someone who could access those resources. In Indonesia, my instructors could not relate to my specific experience as a non-Indonesian woman of color. Instead, they asked me to bring it up to my group mates in order to find the support I needed, placing an undue burden on the other students, who were each struggling in their own ways to navigate our new environment.

Near the end of my experience, I read a book entitled, “The Good Immigrant.” After hearing other POC narratives surrounding discrimination in a new environment, I finally felt seen and heard. During a group meeting, I used this book and critical race theory via presentation to explain my experience to my peers. Hours later, we received notice that we were being sent home due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In the rush to leave that followed, neither my peers nor I had time to process our thoughts on race.

At home, I journaled a lot, especially since I had to quarantine. That summer held major events that helped me heal from the trauma of Bridge Year– America reckoned with race, and Never Have I Ever, one of the few TV shows that centers on a brown girl, debuted its first season on Netflix.

After two years, I have come to terms with my experience. It was painful to grapple with my identity, yet my struggles have prepared me for almost all environments. I have run the gamut of different ways in which I, as a brown girl, will be perceived. Further, I have now intentionally cultivated undying self-respect and love for my skin tone, and by extension, my heritage. I am grateful to have had the experience now, to have reckoned with my race and come to an understanding now, rather than have bottled up the insecurity for the future. My experiences on Bridge Year, even the ugly ones, have allowed me to be a much more mature and confident individual in the spaces I occupy. I am lucky to have that resolve.

Not everyone will have the same experiences I had, even if you fit the same description of a brown Muslim girl. But I wish I had heard this dialogue before going on the trip so that I knew I wasn’t the only one experiencing it. As a pre-frosh on Bridge Year, it’s daunting to navigate resources, send emails, or speak up about these issues. Thankfully, more avenues to access and promote these resources are being implemented, spearheaded by former students. During the year, there will be Peer Advisors who can connect participants with the correct resources. During the application process, feel free to reach out to a Bridge Year Ambassador with any questions you may have.

This experience among other ones is what empowered me to become a Bridge Year Ambassador. In that position, I hope to continue to inform the next generation of students about the complex ways in which different students navigate the experience. I hope that I can make the experience more supportive for future students without discouraging them from considering attending.

In sum, Bridge Year isn’t just a magical experience where you travel to the most beautiful places on earth and end up with a glorious Instagram page. It is a complex, challenging, and meaningful life experience that will shape who you are. That’s what you’re signing up for.