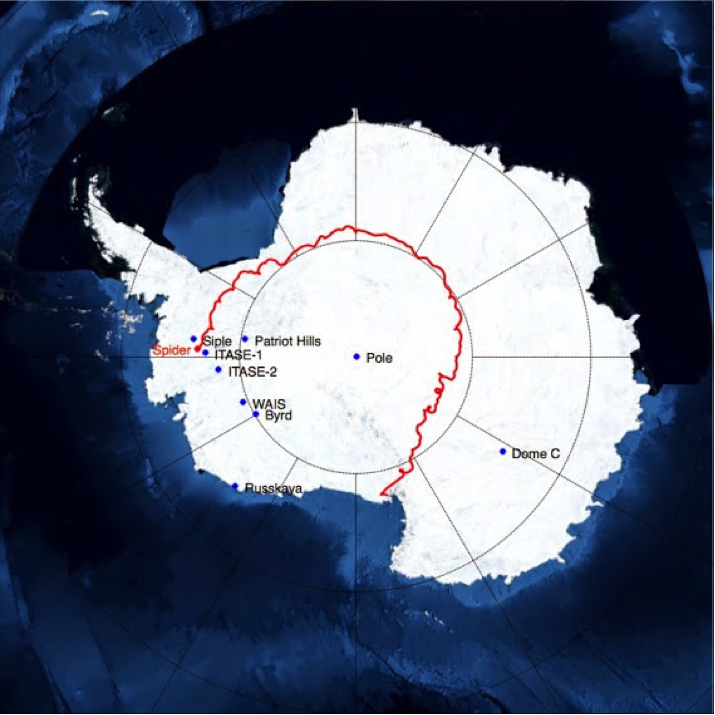

On New Year's Day 2015, at the height of the Antarctic summer, a helium-filled balloon rose into the air, carrying an instrument called SPIDER on a mission to explore how the universe formed. Drifting through the stratosphere about 116,000-feet above the Earth, SPIDER's six cameras collected data that will enable us to look for the characteristic signature of gravitational waves generated in the early Universe.

For me and my team of graduate students and postdoctoral researchers, the balloon launch was the culmination of years of work — about eight, to be exact — and is the product of the efforts of an incredibly dedicated and talented group of individuals. Our team included graduate students, postdoctoral researchers and faculty members from Princeton, the University of Toronto, Case Western Reserve, Caltech and the University of British Columbia. The project was funded largely by a grant from NASA, as well as significant support from the David and Lucile Packard Foundation.

SPIDER is an extremely complex payload, involving autonomous attitude control, pointed star cameras, sub-Kelvin cryogenics, and superconducting detectors. You name it, SPIDER has it. Achieving our science goals requires that each of these subsystems works properly—without any one of them, the science will be compromised.

Ballooning is hard. Really hard. Nobody should ever do anything on a balloon, unless you have to. The team—especially the graduate students and postdoctoral researchers—worked with little tangible reward to design and build an experiment that can extend the horizons of our knowledge to, quite literally, the beginning of time. Then, in a matter of less than a minute, this product of their hopes and dreams, sweat and blood, is violently flung off the end of the launch vehicle and begins its ascent to the edge of space.

But a profound benefit of balloon-borne experiments is that the instrument won't suffer from the noise generated by the Earth's atmosphere. As a result, our receivers are about five times more sensitive than they would be if they were on the ground. That means that one hour of observing in space is as good as a whole day on the ground, all things being equal.

The blog posts below chronicle this journey, from our arrival last October at McMurdo Station, a research center in Antarctica operated by the National Science Foundation, to our recent efforts to recover SPIDER's data after landing. During our months on the ice, members of the team recorded their experiences, which included rebuilding SPIDER (she'd been disassembled for her ocean voyage to Antarctica), preparing her for launch, monitoring her progress and watching anxiously for signs that she made a safe landing.

Our team of Princeton bloggers included graduate student Edward Young, graduate student Anne Gambrel, post-doctoral research associate Jon Gudmundsson and associate research scholar Zigmund Kermish.

"Getting to Ice" by Edward Young, Nov. 9, 2014

"On the Ice!" by Zigmund Kermish, Nov. 15, 2014

"Photos of the Past" by Jon Gudmundsson, Nov. 15, 2014

"SPIDER's Eyes" by Jeff Filipini, Nov. 24, 2014

"Wait, Why am I in Antarctica?" by Zigmund Kermish, Dec. 5, 2014

"Nearing Flight Readiness!" by Zigmund Kermish, Dec. 16, 2014

"Spider Emerges Into the Sunlight" by Zigmund Kermish, Dec. 22, 2014

"SPIDER has Launched!" by Zigmund Kermish, Jan. 3

"Flying" by Anne Gambrel, Jan. 8

"Looking Forward to Recovery" by William C. Jones, Jan. 14

"The End of SPIDER's FLIGHT" by Anne Gambrel, Jan. 19

"We Have Recovered the Data!" by William C. Jones, Feb. 6

"The View From SPIDER" by William C. Jones, Feb. 12

"Now the Fun Begins" by William C. Jones, Feb. 17